|

|

马上注册 与译者交流

您需要 登录 才可以下载或查看,没有账号?立即注册

×

To Find the History of African American Women, Look to Their Handiwork

Our foremothers wove spiritual beliefs, cultural values, and historical knowledge into their flax, wool, silk, and cotton webs.

By Tiya Miles

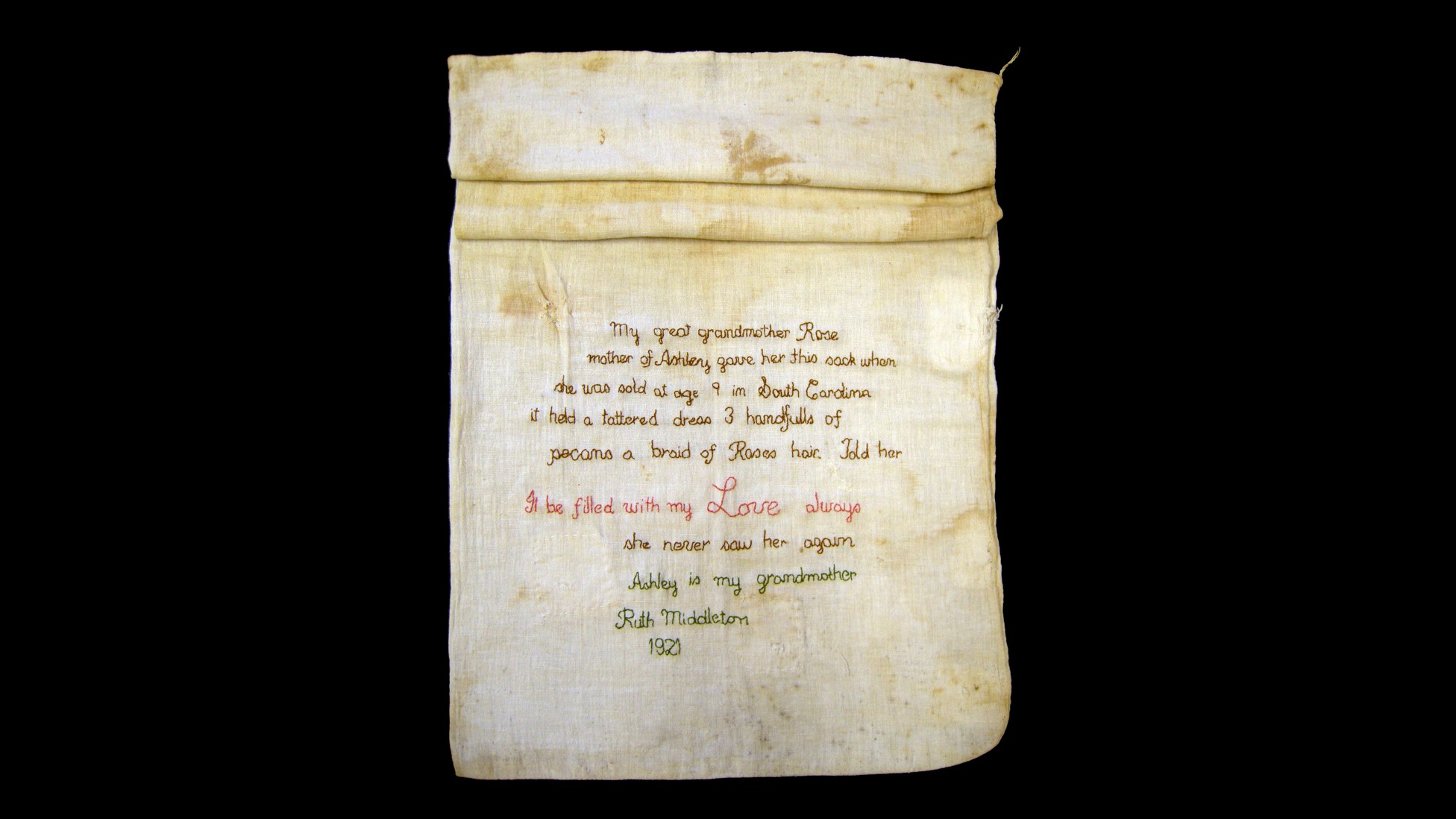

Ashley's sack

Middleton Place Foundation

JUNE 8, 2021

SHARE

About the author: Tiya Miles is a history professor and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. Her latest book is All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake.

Rose was in existential distress that fateful winter in South Carolina in 1852. She was facing the deep kind of trouble that no one in our present time knows and that only an enslaved woman has felt. For Rose understood that, following the death of her legal owner, she or her little girl, Ashley, could be next on the auction block.

Ripping loved ones apart was a common practice in a society structured—and indeed, dependent—on the legalized captivity of people deemed inferior. And sale could not have been the end of Rose’s worries. She must have dreaded what could occur after this relocation: the physical cruelty, sexual assault, malnourishment, mental splintering, and even death that was the lot of so many young women defined as “slaves.” Rose adored her daughter and desperately sought to keep her safe. But what could safety possibly mean at a time when a girl not yet 10 years old could be lawfully caged and bartered?

Read: Stories of slavery, from those who survived it

Rose gathered all of her resources—material, emotional, and spiritual—and packed an emergency kit for the future. She gave that bag to Ashley, who carried it and passed it down across the generations.

That stained antique sack hung in a case at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., from the day of its grand opening in September 2016 until March 2021, and the sack is now on site at the Middleton Place plantation, a national historic landmark in Charleston, South Carolina. The fabric artifact immediately takes hold of those who view it, for on the cotton sack is embroidered an inscription that appears to us like a message in a bottle from across the waves of time:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

The study of the history of African American women is particularly challenging because the keepers of records often overlooked us. The historian Jill Lepore has encapsulated the problem in relation to the wide scope of American history, writing that the “archive of the past … is maddeningly uneven, asymmetrical, and unfair.” So where can historians turn when the archival ground collapses beneath us? To discover the past lives of those for whom the historical record is abysmally thin, I’ve found that we must expand the materials we use as sources of information.

Book jacket of All That She Carried.

This post is excerpted from Miles’s recent book.

Though early women’s history can be elusive, women need not “conjure a history for ourselves,” the archaeologist Elizabeth Wayland Barber says. “Here among the textiles,” she writes, “we can find some of the hard evidence we need.” The historian Elsa Barkley Brown wrote that if we “follow the cultural guides which African American women have left us,” we will “understand their worlds.” Our foremothers wove spiritual beliefs, cultural values, and historical knowledge into their flax, wool, silk, and cotton webs. The work of their hands can lead us back to their histories, and serve as guide rails as we grope through the difficult past.

Many of us feel connected to history through women’s handiwork. Some save and repair hand-me-down table linens. Others hunt flea-market aisles for vintage fabrics. A few of us learn the skills of traditional sewing and quilting to reproduce the experience and art of our foremothers. The past seems to reach out to us through these fabrics and the practices of making them that have survived over time. Gathered up like the crisp ends of a cotton sheet fresh from the wash, past and present seem to meet above the fold.

Ashley’s sack is an extraordinary artifact of the cultural and craft productions of African American women. But it is not just an artifact. It is an archive of its own, a collection of disparate materials and messages, at once a container, carrier, textile, art piece, and record of past events. The lives of three ordinary African American women—Rose, Ashley, and Ruth—spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, slavery and freedom, the South and the North. Their love story as told through this sack is one of sacrifice, suffering, lament, and the rescue of a tested but resilient family lineage.

RECOMMENDED READING

A dad watches his daughter grow up

Dear Therapist: I Looked Through My Daughter’s Phone, and I Didn’t Like What I Saw

LORI GOTTLIEB

The Digital Ruins of a Forgotten Future

LESLIE JAMISON

A pyramid balances on its point, upside down, in the desert with blue sky and 3 small figures

Human History Gets a Rewrite

WILLIAM DERESIEWICZ

Rose exemplifies the collective experience of enslaved Black women, who preserved life when hope seemed lost. Rose’s kit was, by all evidence, one of a kind, but she shared with other women in her condition a vision for survival that required both material and emotional resources. She sought to immediately address a hierarchy of needs: food, clothing, shelter, identity through lineage, and, most centrally, an affirmation of worthiness. Rose gathered a dress, nuts, a lock of hair, and the cotton tote itself—things shaped by the intermingling of southern nature and culture. These items show us what women in bondage deemed essential, what they were capable of getting their hands on, and what they were determined to salvage. Rose then sealed those items, rendering them sacred, with the force of an emotional promise: a mother’s enduring love.

Read: A priceless archive of ordinary life

Despite mother and daughter’s separation, the bond between them held longevity and elasticity, traversing the final decade of chattel slavery, the chaos of the Civil War, and the red dawn of emancipation before finding new expression in the early 20th century, as a baby girl, Ruth, Ashley’s granddaughter, was born.

Just as remarkable as this story is how we have come to know about it. Through her embroidery, Ruth ensured that the valiance of discounted women would be recalled and embraced as a treasured inheritance.

A granddaughter, mother, sewer, and storyteller imbued a piece of old cloth with all the drama and pathos of ancient tapestries depicting the deeds of queens and goddesses. She preserved the memory of her foremothers and also venerated these women, shaping their image for the next generations. Without Ruth, there would be no record. Without her record, there would be no history.

Aptly called a “revelation” by Jeff Neale, a museum interpreter at the Middleton Place plantation, Ashley’s sack illuminates the contours of enslaved Black women’s experiences, the emotional imperatives of their existences, the things they required to survive, and what they valued enough to pass down. “The things we interact with are an inescapable part of who we are,” as the historian of the environment Timothy LeCain has put it, and hence things become our “fellow travelers” in this life.

Every turn in the sack’s use—from its packing in the 1850s to its tending across the dawn of a century to its embroidering in the 1920s—reveals a family endowment that stands as an alternative to the callous capitalism bred in slavery. As the women in Rose’s lineage carried the sack through the decades, the sack itself bore memories of bondage and bravery, genius and generosity, longevity and love.

This textile has an effect subtler yet more moving than that of any monument. Ashley’s sack is a quiet assertion of the right to life, liberty, and beauty even for those at the bottom, and stands in eloquent defense of the country’s ideals by indicting its failures.

This post is excerpted from Tiya Miles’s book All That She Carried: The Journey Of Ashley's Sack, A Black Family Keepsake.

Tiya Miles is a history professor and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. Her latest book is All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake.

要寻找非裔美国妇女的历史,请看她们的手工作品

我们的祖先将精神信仰、文化价值和历史知识编入她们的亚麻、羊毛、丝绸和棉花网。

作者:蒂亚-迈尔斯

阿什利的麻袋

米德尔顿广场基金会

6月8日, 2021

关于作者。蒂亚-迈尔斯是哈佛大学拉德克利夫高级研究学院的历史教授和拉德克利夫校友教授。她的最新著作是《她所携带的一切》。阿什利的麻袋的旅程,一个黑人家庭的保留品。

1852年南卡罗来纳州的那个命运之冬,罗丝正处于生存困境。她面临着我们这个时代没有人知道的、只有被奴役的妇女才会感受到的那种深层麻烦。因为罗丝明白,在她的合法主人死后,她或她的小女儿阿什利可能是下一个被拍卖的对象。

在一个由被认为是低等人的合法囚禁构成的社会中,拆散亲人是一种常见的做法,事实上也是一种依赖。而出售不可能是罗丝担心的终点。她一定很害怕这次搬迁后可能发生的事情:身体上的虐待、性侵犯、营养不良、精神分裂,甚至死亡,这是许多被定义为 "奴隶 "的年轻女性的命运。罗丝很爱她的女儿,拼命地想保护她的安全。但是,在一个未满10岁的女孩可以被合法地关在笼子里并进行交易的时代,安全可能意味着什么?

阅读:奴隶制的故事,来自那些幸存的人

罗丝收集了她所有的资源--物质的、情感的和精神的,并为未来准备了一个应急包。她把那个袋子给了阿什利,阿什利带着它,代代相传。

那只染色的古董袋从2016年9月史密森尼国家非洲裔美国人历史和文化博物馆盛大开馆那天起,一直挂在华盛顿特区的一个箱子里,直到2021年3月,现在这只袋子在南卡罗来纳州查尔斯顿的国家历史地标--米德尔顿广场种植园现场。这个织物工艺品立即吸引了那些看到它的人,因为在棉布袋上绣着一个铭文,在我们看来,它就像一个来自时间浪潮的瓶中信息。

我的曾祖母罗斯

阿什利的母亲在她9岁时被卖到南方时给了她这个麻袋。

她9岁时在南卡罗来纳州被卖掉

里面装着一件破烂的衣服 3把胡桃

山核桃,以及罗丝的头发辫子。他告诉她

它将永远充满我的爱

她再也没有见到她了

阿什利是我的祖母

露丝-米德尔顿

1921

对非裔美国妇女历史的研究尤其具有挑战性,因为记录的保存者往往忽略了我们。历史学家吉尔-莱波尔(Jill Lepore)结合美国历史的广泛范围概括了这个问题,他写道:"过去的档案......令人疯狂地不均衡、不对称和不公平"。那么,当档案地在我们脚下坍塌时,历史学家可以转向哪里?为了发现那些历史记录极其单薄的人的过去生活,我发现我们必须扩大我们作为信息来源的材料。

All That She Carried》的书皮。

这篇文章节选自迈尔斯最近的书。

尽管早期妇女的历史可能是难以捉摸的,但妇女不需要 "为自己创造一段历史",考古学家伊丽莎白-韦兰-巴伯说。"她写道:"在这些纺织品中,我们可以找到一些我们需要的确凿证据"。历史学家Elsa Barkley Brown写道,如果我们 "遵循非裔美国妇女留给我们的文化指南",我们将 "理解她们的世界"。我们的先辈们将精神信仰、文化价值和历史知识编织在她们的亚麻、羊毛、丝绸和棉花网中。她们手中的工作可以引导我们回到她们的历史,并在我们摸索困难的过去时作为指导性的轨道。

我们中的许多人通过妇女的手艺感到与历史相连。有些人保存并修理手头的桌布。其他人则在跳蚤市场的过道上寻找复古织物。我们中的一些人学习传统的缝纫和绗缝技能,以重现我们祖先的经验和艺术。过去似乎通过这些织物和随着时间流逝而流传下来的制作方法向我们伸出手来。就像刚洗完的棉被的清脆的两端一样,过去和现在似乎在折叠处相遇。

阿什利的麻袋是非洲裔美国妇女的文化和工艺产品的一个非凡的人工制品。但它不仅仅是一件工艺品。它本身就是一个档案,是不同材料和信息的集合,同时是一个容器、载体、纺织品、艺术作品和过去事件的记录。三个普通的非裔美国妇女--罗斯、阿什利和露丝的生活跨越了19和20世纪,跨越了奴隶制和自由,跨越了南方和北方。通过这只麻袋讲述的她们的爱情故事是一个牺牲、苦难、悲叹,以及对一个经过考验但有弹性的家族血统的拯救。

推荐阅读

一位父亲看着他的女儿长大

亲爱的治疗师。我翻看了女儿的手机,但我不喜欢我看到的东西

罗莉-戈特利布(LORI GOTTLIEB

被遗忘的未来的数字废墟

LESLIE JAMISON

一座金字塔在沙漠中倒立平衡,蓝色的天空和三个小人物。

人类历史得到重写

威廉-德雷谢维奇(William Deresiewicz

罗斯体现了被奴役的黑人妇女的集体经历,她们在似乎失去希望的时候保存了生命。从所有证据来看,罗丝的装备是独一无二的,但她与其他与她处境相同的妇女一样,有一个需要物质和情感资源的生存愿景。她试图立即解决一系列的需求:食物、衣服、住所、通过血统获得的身份,以及最重要的,对价值的肯定。罗斯收集了一件衣服、坚果、一绺头发和棉质手提箱本身--这些东西是由南方自然和文化的交融而形成的。这些物品向我们展示了被奴役的妇女认为必不可少的东西,她们有能力得到的东西,以及她们决心要挽救的东西。然后,罗丝将这些物品封存起来,使其成为神圣的,具有情感承诺的力量:一个母亲永恒的爱。

阅读。平凡生活的无价档案

尽管母女分离,她们之间的纽带却保持着长久的生命力和弹性,穿越了动产奴隶制的最后十年、内战的混乱和解放的红色黎明,然后在20世纪初找到了新的表达方式,因为一个女婴,即阿什利的孙女露丝出生了。

与这个故事同样引人注目的是我们是如何知道这个故事的。通过她的刺绣,露丝确保了打折妇女的英勇事迹将被回顾和拥抱,成为一份珍贵的遗产。

一个孙女、母亲、缝纫师和讲故事的人将一块旧布赋予了所有描绘女王和女神事迹的古代挂毯的戏剧性和悲怆性。她保留了对她先辈的记忆,同时也崇敬这些女性,为下一代塑造她们的形象。没有路得,就没有记录。没有她的记录,也就没有历史。

米德尔顿广场种植园的博物馆讲解员杰夫-尼尔恰当地称之为 "启示",阿什利的麻袋照亮了被奴役的黑人妇女的经历的轮廓,她们生存的情感需要,她们生存所需的东西,以及她们看重的足以传承的东西。正如环境史学家蒂莫西-勒凯恩(Timothy LeCain)所说,"我们与之互动的东西是我们是谁的一个不可避免的部分",因此,东西成为我们今生的 "同路人"。

麻袋使用的每一个转折--从19世纪50年代的包装到跨世纪的打理,再到20世纪20年代的刺绣--都揭示了一种家庭的禀赋,它是奴隶制下孕育的冷酷资本主义的替代品。随着罗丝家族中的女性带着麻袋走过几十年,麻袋本身也承载着对束缚和勇敢、天才和慷慨、长寿和爱的记忆。

这种纺织品具有比任何纪念碑更微妙却更动人的效果。阿什利的麻袋是对生命、自由和美丽的权利的无声宣示,即使是那些处于底层的人也是如此,并通过起诉国家的失败来雄辩地捍卫国家的理想。

这篇文章节选自Tiya Miles的《她所携带的一切》一书。阿什利的麻袋的旅程,一个黑人家庭的纪念品。

蒂亚-迈尔斯是哈佛大学拉德克利夫高级研究学院的历史教授和拉德克利夫校友教授。她的最新著作是《她所携带的一切》。阿什利的麻袋的旅程,一个黑人家庭的纪念品。 |

|

|网站地图|手机版|小黑屋|关于我们|ECO中文网

( 京ICP备06039041号 )

|网站地图|手机版|小黑屋|关于我们|ECO中文网

( 京ICP备06039041号 )